In the late nineteenth century, the size and number of poverty-stricken slums in American cities exploded at an alarming rate. These slums had grown out of both the country’s rapid transformation into an industrial power following the American Civil War and from the arrival of a massive wave of unskilled southern and eastern European immigrants – with over five million arriving in the 1880s alone. And since it contained America’s preferred port of immigration, Ellis Island, New York City became the epicentre of this demographic change as its population increased by over 25% in just over a decade. Even though slum dwellers made up a large portion of the population in cities like New York, they went almost unnoticed by members of the American middle and upper classes as cities who rarely ventured into their cities’ poor neighbourhoods. The conditions in which slum dwellers lived were crowded, unsanitary, dangerous, and often without access to basic amenities like electricity or clean water. Evidence of people living in this type of squalor could be found in nearly every major city, yet it was almost never mentioned in the media except to shed light on recent crimes. Its presence in popular culture was no different where the only attention paid to the urban poor could be seen in the more romantic novels of James Joyce and Charles Dickens. While there were some poverty relief programs in American cities at the time, they mostly operated on a local level and provided short-term solutions instead of drawing attention to larger systemic problems. With many of those in a position to help largely unaware of the conditions in slums and those living in them too disenfranchised to help themselves, American slums remained paradoxically both invisible and omnipresent.

Decades, these American slums continued to fester with little outside attention or intervention. But in 1890, a pioneering photojournalist and ‘muckraker’ named Jacob Riis published an in depth look at New York’s slums titled How the Other Half Lives. Riis’ book became popular almost immediately and received high praise from The New York Times and soon to be president Theodore Roosevelt. More important than praise, however, was the urban reform it helped inspire, including the formation of the Tenement House Committee in 1894 which provided a governmental body to represent slum dwellers and the New York Tenement House Acts of 1895 and 1901 which officially defined slums and outlawed rear tenement housing and put regulations on ventilation, light, fire safety, and general space for living areas.

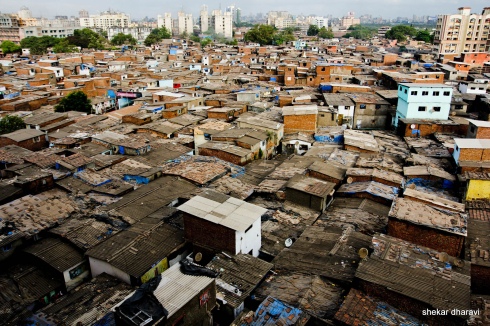

Today, urban poverty continues to exist in many of these same cities of the Northern Hemisphere like New York. These neighbourhoods, however, hardly resemble the slums of the nineteenth century. But slums are here to stay, and over the past seventy years slum-life has grown exponentially across the cities of the developing world and is estimated to contribute to around 95% of global population growth this decade. Not only are today’s slums growing at a rate unprecedented in any population in human history, but they are also a widespread and global phenomenon with over 15,000 unique slums existing in more than 600 cities across the Earth. Much like the American slums of the nineteenth century, many modern slums have been pushed to the least desirable and more isolated parts of cities, allowing them to be segregated from and easily forgotten by the cities’ ruling classes. And, much like the slums of the nineteenth century, today’s slums are almost without representation in media and popular culture. When we do choose to represent them visually, they are often seen in world news at grand, birds-eye views which not only make the slums difficult to distinguish, but also remove any agency from their inhabitants by effectively shrinking them to the size of ants. When there are ‘close-up’ depictions of slum dwellers which may attempt to give agency to their subjects, they are rely on the romantic traditions of Dickens and Joyce instead of the realist and voyeuristic ones of Riis.

Slum dwellers today are once again caught between living both everywhere and nowhere. We are partially aware of their existence, but only to the extent that it entertains us and almost never in its true scale or dereliction. Most importantly, it seems that little effort has been taken to fight modern global urban poverty. By undertaking a diachronic comparison of late nineteenth century and present day slums, this project aims to assess the successes and failures of these representations in attracting larger awareness and intervention.