In this essay, I intend to portray a transnational history of the territory of Neutral Moresnet that demonstrates its nature as being representative of wider trends taking place in the multinational region of Lotharingia.

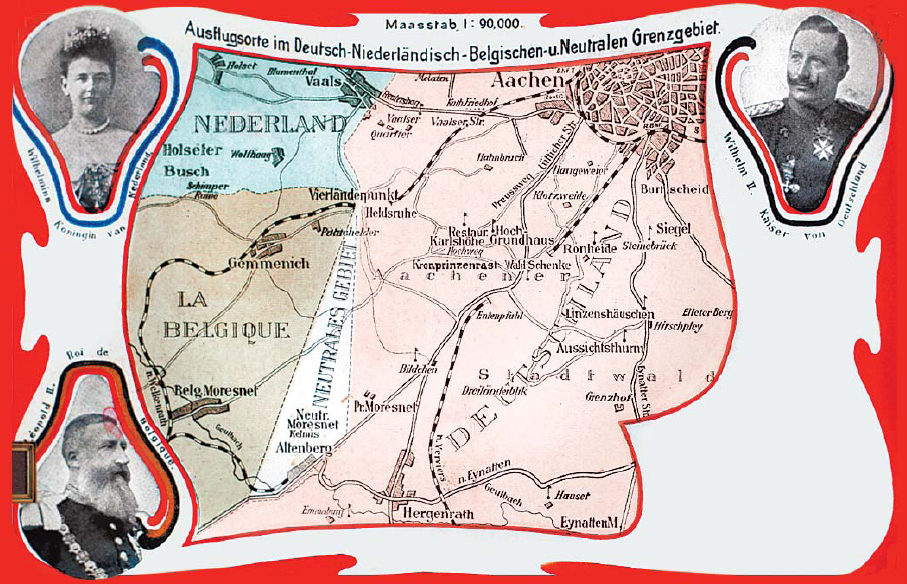

The territory of Neutral Moresnet, a small triangular territory, located at the modern-day tri-border point between the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium, was given neutral status and a degree of autonomy at the end of the Congress of Vienna in the interest of the Balance of Power, a concept that was of prime importance in European geopolitics in 1815, and indeed for most of the nineteenth century. As no agreement reached over whether the Kingdom of the Netherlands or the Kingdom of Prussia would receive the territory including a strategically-important zinc spar mine, the territory surrounding the mining town of Kelmis was left out of the agreements surrounding the congress, and it stayed neutral until 1914, when it was occupied by Germany in the First World War. Following the war, the territory was quietly ceded to Belgium. However, during its relatively short history, there were a number of events that took place within this small territory that make it something of a microcosm of the region surrounding it, and a mirror of trends taking place in the surrounding area during the nineteenth century. A series of quasi-nationalistic expressions, for example, were expressed by Moresnetians during the century: In 1848, local coins were minted, though they were not the official currency of the territory, which used French francs. In 1883, a tricolour flag was designed, and in 1886, local stamps were printed – a seemingly unnecessary public service in a country containing just one small town. In 1908, after the zinc mine was exhausted in 1885, the town’s doctor, Wilhelm Molly, proposed turning Neutral Moresnet into the world’s first Esperanto-speaking state, giving it a national language, and the townspeople were given free lessons, a rally was held, a national anthem was written in Esperanto, and the town was renamed Amikejo. The World Congress of Esperanto named Neutral Moresnet the world capital of the Esperanto community that same year.

It can be tempting, however, to simply dismiss the history of Neutral Moresnet as an interesting Wikipedia page, but an inconsequential footnote within a wider historical (and specifically transnational) conversation. As mentioned earlier, the events that took place in Neutral Moresnet were representative of wider, transnational trends taking place across Europe during the ‘long nineteenth century’, and more specifically in the area which can be called Lotharingia: the Rhineland, Alsace-Lorraine, Belgium and the Netherlands. Besides the circumstances of its birth, rooted in the dominant geopolitical concept of the Balance of Power, Moresnet’s nationalistic expressions are responses to the Nationalism that swept across the surrounding area – see the independence of Belgium in 1830, or the revolutions of 1848, which took place over most of Europe, including Belgium, Germany and France, or the development of German nationalism until 1871. This trend manifests itself in Neutral Moresnet in the invention of a Moresnetian national identity, of coins, a flag, and a national language. This last point of language also offers an interesting dichotomy – Esperanto, an internationalist constructed language being used for a nationalistic purpose seems somehow wrong, but I would argue that the adoption of this language, as well as the adoption of national symbols, were an attempt by Neutral Moresnetians to assert their relevance, legitimacy and modernity in Europe as citizens of a small, semi-autonomous and now resource-poor state subject to several attempts at repatriation into either the Netherlands, Belgium or Germany over the course of its century-long history.

Neutral Moresnet’s intriguing, oddball nature, as well as a relative lack of historical inquiry into it is something of a double-edged sword. On one hand, it offers me a lot of freedom in pursuing this topic, but on the other, there is somewhat of a dearth of academic literature, at least in English, for me to work off of. However, I think that Neutral Moresnet’s transnational nature, location at the confluence of three language zones and strong connection to the trends and forces that shaped nineteenth-century Europe make it an ideal location for an essay in transnational history, and I’m very much looking forward to writing it.