Stefan Nygård

Stefan Nygård, European university institute & University of Helsinki

My current post-doctoral research, which is part of a collective project on “Asymmetries in the European intellectual space” (Academy of Finland), deals with the sociocultural history of intellectuals and intellectual spaces in the Northern European periphery, 1870-1940. I argue that intellectuals in geocultural and linguistic peripheries have by necessity been transnational in specific ways. The intellectual fields in these countries were characterized by a limited degree of self-sufficiency and autonomy. Specialization in a certain field was possible only to a certain extent and many experienced the strong national imperative in these countries as a constraint to intellectual freedom. Peripheral intellectuals sought to compensate for their predicament by making symbolical alliances with groups and individuals elsewhere and seeking professional recognition abroad, as well as other ways of mobilizing internationality. Even those who never physically left their national intellectual fields had the option of positioning themselves as “local cosmopolitans”, stressing their membership in an international intellectual community. This space was characterized by a tension between on the one hand the egalitarian notion of a republic of letter where everyone participates on equal grounds, on the other hand the inevitable geocultural hierarchies at play also in the international intellectual exchange: there were centre-periphery dynamics involved in the interaction between intellectual fields, there were limits to intellectual transnationalism, and transfers were more often characterized by asymmetry than reciprocity.

In this situation, a considerable number of those Nordic intellectuals that participated on international arenas positioned themselves as cultural mediators between dominant fields: the Danish 19th century critic Georg Brandes, a “literary kingmaker” of his time, between English, German and French literature and philosophy, his Norwegian contemporary Henrik Ibsen between Scandinavian, German and French theatre, and, more recently, the Finnish and Norwegian philosophers Arne Naess and G. H. von Wright between analytic and “continental” philosophy. In the 1870s Brandes had based his role as a mediator between dominant fields on the insight that important writers and philosophers such as J. S. Mill were largely ignorant of rivalling traditions, German philosophy in the Mill’s case. He came to the conclusion that small country intellectuals should make an effort to explore the innovative potential of bringing together parallel developments. Peripheral actors are attracted by this kind of mediation because it strengthens their voice on international arenas, much in the same way as the Scandinavian states approached international politics in the twentieth century. And small countries may be particularly well suited for the task. As “translation cultures” they pay close attention to developments abroad and adjust themselves to external demands.

My project looks both at the significance of small country peripheries for the functioning of the European intellectual space as a whole, and the way this space has been mobilised locally. Of particular interest for discussing the implications of geocultural differences is the extent to which actors from the centres and the peripheries conceptualised transnational spaces differently. If the cores were characterized by a tendency towards universalising local discourses, peripheral actors were by necessity immune to universalism and sensitive to the hierarchies involved in cultural transfers and international communication. A recurring pattern in the way the intellectuals I study positioned themselves is an entanglement of spatial and temporal dimensions. Modernity and the “real discussions” were presumed to be taking place elsewhere, and cosmopolitan intellectuals in the peripheries fashioned themselves as local accelerators of progress, by associating themselves with the avant-gardes of European cultural capitals. Each discipline and discourse was characterized by specific centre-periphery dynamics. A late 19th century Finnish philosopher would conceive of Copenhagen as the regional semi-centre, German academy as the main target of academic publications, and France, or Paris, as the ultimate source of symbolic capital.

These are examples of questions that my research deals with. I have produced a number of articles on the topic, and have attached on of them (co-written with a colleague in philosophy). Currently, I am working on turning some of these articles into a book manuscript. Visualisation has not yet been a part of my research yet, but “spaces” and “fields” being key concepts, I am convinced that maps and visualisations would enhance my analysis. For the purpose of this workshop, I would like to discuss this potential in relation to Georg Brandes, mentioned above. The idea is to see e.g. if my argument that peripheries have a specific role in keeping the wider European intellectual space together, can be demonstrated with the help of maps and network diagrams, based on the correspondence of Brandes and wih the help of social network analysis. Brandes, I think, would be a good choice for such a study for several reasons: his letter archives are massive; he was widely recognised in Europe as one of the most influential intellectual networkers of his time; his own works were broadly diffused and translated in Europe and beyond, and he played an active role in the cultural fields of several countries. Moreover, his career illustrates the complex logics of culturals transfers. Two random examples: He played a central role in introducing Tolstoj and the Russian novel in Paris in the 1880s, after having lectured on the subject in Helsinki on his way back from Moscow and St Petersburg. And he was influential in introducing the liberalism of J. S. Mill in Scandinavia, but curiously through an Italian filter, inspired by the pragmatic approaches to Mill of Italian liberals in Rome and Florence.

While these considerations relate to the circulation of intellectuals and their texts in space, another dimension of the project would be to look at how space is represented in Brandes’ work. His literary histories are filled with spatial-temporal metaphors of progress, emphasising the gap between Scandinavian backwardess and the modernity of the European cultural centres, and his own role as the accelerator of progress in the periphery. But he shifts between roles and this perspective disappears when he acts as the proud ambassador of Scandinavian culture abroad.

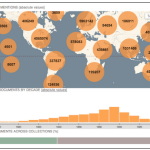

Visualisation for discussion:

“European diffusion of French novels”, in Franco Moretti, The Atlas of the European novel 1800-1900 (1998). The maps demonstrate the unified reading patterns in 19th century Europe, as well the modest contemporary success of realist novels (Stendhal, Balzac) in comparison with more melodramatic novels of Hugo, Dumas etc.

Further material:

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

Dear Stefan,

we found the abstract very inspiring because the concept of “Assymmetries in the intellectual space” highly applies to the Hungarian intellectuals before 1848 as well. In our findings we came across the interesting fact that these intellectuals (e. g. Zipser, Rumy etc.), use periodicals in different countries and in different languages, in order to achieve transnational recognition. Surprisingly they do not even hesitate to extensively use entertainment journals (which are at the core of our research interest) as their platform.

Dear Stefan,

Thanks for this abstract – it’s very interesting to me, although it is not a topic I know much if anything about.

I was wondering what type of connections you wanted to visualise? For example, as a basic start, would you have a list of the people in Europe that Brandes corresponded with, and their locations, as well as volume of correspondence, and do you think you could plot this onto a map? Or equally, specific data on publication levels of his work?

Looking forward to hearing more about this!

Georgina