Josef Grna (1880-1918)

by Bernhard Struck

Pardubice. Kutna Hora. Svitavy. Jevicko. Hradec Kralove. Smichov. Have you ever heard of any of these places? Worry not, me neither – at least not until recently. Let us start with and in Smichov. In 2020, the ESF generously funded my project “Local Internationalist? Bohemia and Central European Esperantists between the local, national, and global (1880s-1920)”. In late August 2020 I arrived in Prague 5 or Smichov.

The district is proper Prague, away from the more scenic, touristy city centre and Old Town. Today, Smichov is a slowly gentrifying yet visibly former working-class district. For me it was conveniently located. I could hop either directly onto the bus that took me to the outskirts of Prague to the National Archives and the City Archives or straight to the city centre to the National Library or to the Museum and Archive of Czech Literature. I settled in well until Covid became the main news again by September. With the news of a strict lockdown looming, my trips to archives became slightly more hectic and pragmatic: going through files fast and taking pictures as fast as I could – grab-and-run archive visits. Then the hard lockdown came in early October. And hard meant: archives were closed. But I had shot my photos and started sifting through them. In between I took breaks and walked Smichov. On one of my afternoon walks through Smichov I came across the statue of Jakub Arbes. The name rang a distant bell.

But what had brought me to (Esperanto in) Prague and Bohemia in the first place? Well, the places mentioned above. My own entry into the history of Esperanto were the annual congresses starting with Boulogne-sur-Mer in 1905 to the Paris congress in 1914. From an attempt to get a grasp of the geographical distribution of congress attendees some – to me surprising – regional clusters emerged. Among them was Bohemia and with it came questions. Why would people in places like Holice, Pardubice or Jevicko learn Esperanto in 1905? These were not quite the places where I expected the early Esperanto movement to flourish. After all these were all more provincial cities dotted around Prague. And who were these people around 1910?

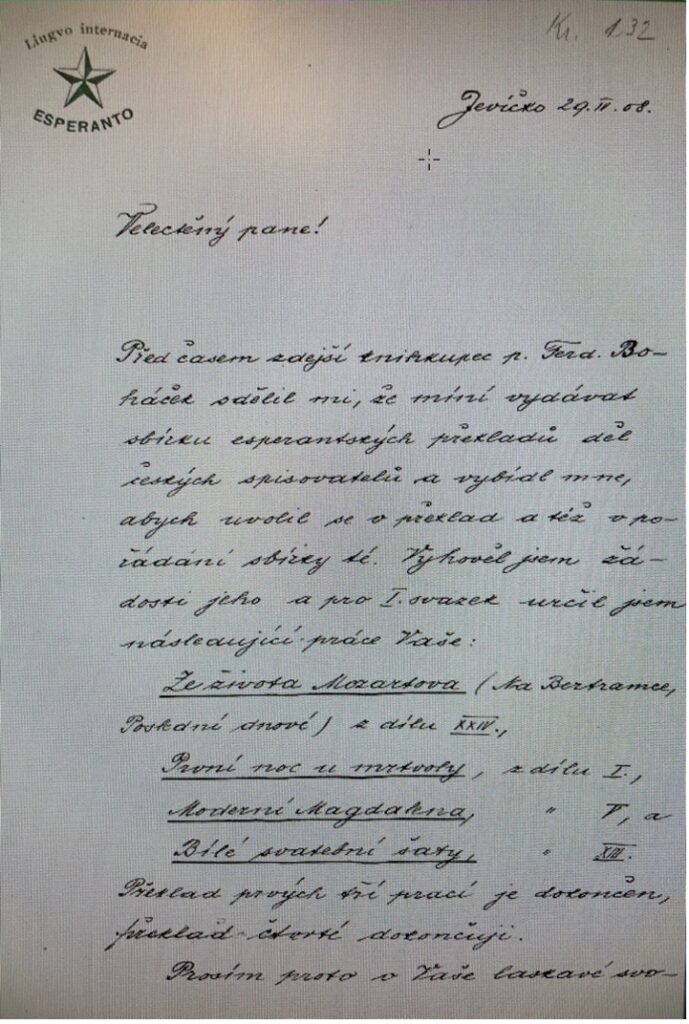

Jevičko is situated just north of Brno home to the first Esperanto club in Bohemia in 1901. Just northwest of Jevičko we find other early clubs in places like Pardubice and Kutna Hora. These are the hometowns of several of the pioneers and early activists of the Bohemian movement such as Theodor Cejka or Stanislav Schulhof. Many of these early Bohemian Esperantists were teachers at local high schools. And while a place like Jevičko at first sight seems to be a remote hinterland, it was not. From the letters Grna sent to Arbes it becomes evident that all these Esperantists were well connected, in constant communication, and onto something.

In 1908 when Grna approached Arbes a certain Franz Kafka was just about to start his literary career in Prague. While less known than Kafka internationally, Jakob Arbes was no stranger in Czech literature. In fact, he was a household name who had come to fame in the 1860s and 1880s. Josef Grna approached Arbes in April 1908 with the suggestion to translate some of “his literary gems” into Esperanto. Grna had discussed this move with fellow teachers and Esperantists as well a local bookseller and publisher from Jevičko, Ferdinand Bohaček – another local Esperantist. And so, in 1910, some of Arbes’ Czech literary works including “Moderní Magdalena” (Modern Magdalena) and “Ze zivota Mozartova” (From the Life of Mozart) were published with Hachette in Paris under the title “Rakontoj”. It was the first translation of Czech literature into Esperanto.

What is remarkable about this? And what does this tell us about Esperanto in Bohemia around 1910? Of course, a statue, some letters, browsing through Bohemian Esperanto journals, and some local Esperantists cannot tell the full story of the language in Bohemia at the time. But these snippets are part of a bigger picture and pattern. Highschool teachers stand out as part of the wider socio-professional profile among Esperantists in the region. And if we accept that education is closely linked to the idea of the nation and a tool for nation-building, these Esperanto-speaking teachers were onto something. They saw Esperanto as a means to showcase Czech literature to the wider world. Esperanto, for them, was the means to popularise the literary works of a “small nation” in a much larger and rapidly interconnecting and globalising world around 1910.

Today, an author like Jakub Arbes may not resonate with readers beyond the Czech Republic. Yet back then his novels stood for Czech culture, literature, and nationalism. Arbes’ works were among the first to be translated. And it may have been a very deliberate choice. He was a journalist and was editor of several political journals including Hlas (The Voice). His writing, his political activism including close contacts to the so-called Májovci, a post 1848 literary circle that opposed Viennese-Habsburg rule, led to persecution, a 15 month prison sentence and, ultimately, as a consequence time in French exile.

While we may associate Esperanto with internationalism, collaboration in sciences and the peace movement – to name just a few – the Arbes-Grna correspondence hints at another facet that may be particular to Bohemia, other small nations or other regions defined by tensions between state and region, between nationalism, between dominant language of empire (German) and Czech in this case. My research is still work in progress yet actors like Josef Grna may have been both: local internationalists and nationalists.