It is well known that the first Esperantists were mostly well-educated men with the means and resources to learn the constructed language and contribute to the movement. In countries like Spain and Portugal, where illiteracy rates were higher than in most European regions, access to a language that was initially experienced in writing was therefore an almost unsurmountable barrier. The fact that by 1928 there had been 1,116 Esperantists registered the peninsula shows, however, that Esperanto proved to be capable of taking root in both countries. But who were these people? Compiling information from kongresolibroj, adresaroj, and journals published between 1887 and 1928, a comprehensive database listing their professions, places of birth and death, addresses, and the congresses they attended has been created. These are the highlights.

The following names are spelled as they appear in the original primary sources.

Women and Esperanto

A quick look at the leading figures of Iberian Esperantism in the early twentieth century demonstrates that men were a predominant feature of the movement. Ricardo Codorniu y Stárico, José Rodríguez Hiertas, Vicente Inglada, Frederic Pujulà i Vallès, Delfi Dalmau, Julio Mangada Rosenörn, Jorge Aníbal Saldanha Carreira, and Bernardino Martins d’Almeida among others played a crucial role in the development and popularity of the constructed language in the region. This male preponderance was not limited to the pioneers, but also present among Esperantists who were part of the project in less noticeable ways. Indeed, out of the 1,116 Iberian Esperantists registered between 1887 and 1928 that we have records of, 966 were men, 123 women, and 26 did not disclose their gender.

Although male dominance was widespread, some places presented anomalies in their numbers. In Ireland, for example, Esperanto seemed to have been particularly popular among schoolteachers, a predominantly female profession. Between 1905 and 1924, twenty-five Irish individuals travelled to different Universal Congresses, with thirteen of them being women. Even if when compared to the Irish case Iberian female Esperantists were not as numerous, they still made significant contributions to the movement. In Portugal, Laura Rodrigues and Adelaide Ribeiro were Portugala Revuo’s editors. In Spain, they penned short pieces and translations, such as those authored by María Julivert for Hispana Esperantisto.

A variety of professions

Not many listed their professions when registering for events, and it can be assumed that some might have changed careers between 1887 and 1928, especially when it came to those that identified themselves as students. However, there were some clear trends among those who did reveal their jobs. Members of the church were particularly present in Spain, as twenty-eight of them have been linked to the Esperantist activities carried out during this time. Ricardo Albiol Aguilar from Valencia and Anton Bach from Tarrasa were among those who wrote down “church” or any other variations under their names in Spain, whereas Albano Falcão from Bragança and Manoel José Fernandes from Arcos de Valdevez were Portuguese priests.

Moreover, there was a significant number of lawyers involved in the movement. At least fifteen explicitly stated to be Spanish lawyers, like Julio Escauriaza from Bilbao and José Feo Cremades from Valencia. Many simply claimed to be businessmen, more specifically twenty-two Spanish Esperantists did so, such as José Pinell Mas from Sabadell and Pedro Naranjo Terán from Jerez.

At least ten claimed to be part of the army, six were engineers, eleven were physicians, six students, six bankers, and eleven teachers in Spain. In Portugal, teachers and doctors were a majority. These numbers, of course, do not represent the reality of the movement, as only a minority shared their profession.

There were, however, a few curious professions among those that made it to the records. Isidore Achón-Gallifa from Zaragoza was a bookbinder, Rafael Caplliure-Ballester from Valencia was a draughtsman, Narciso Escuin Valls from Valencia was a stenographer, and Mister Ferri, whose address and first name remain unknown, was a dog racing official specialized in dalmatians. In Portugal, Bento Faria identified as a poet and dramaturg.

Painters, politicians, and pharmacists were also present in Esperantism, showcasing the diversity of a movement that welcomed anyone regardless of their economic and social background.

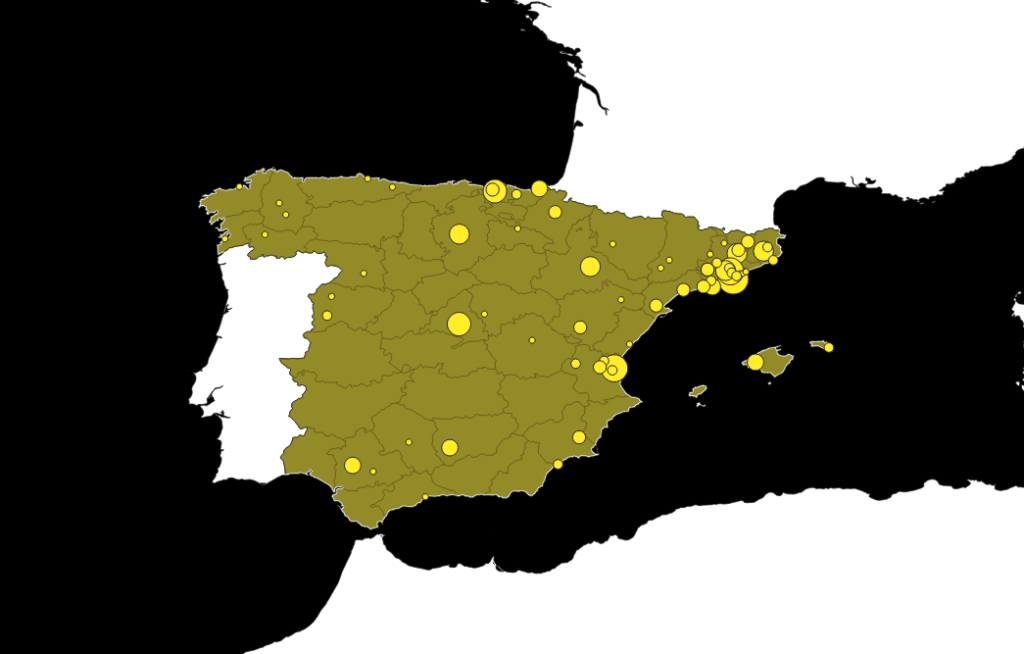

Esperantists from all over the Peninsula, but not really

Although by 1928 Esperanto was well-spread through the region, there were still regions where the constructed language had not flourished, whereas it was thriving in others. Of course, urban centers attracted most speakers, not only because of population density, but also due to resources. This meant that the most developed areas in both Portugal and Spain were home to blooming regional and local Esperanto communities.

The two following simplified maps show the place of residence of most Iberian Esperanto-speakers in the early twentieth century. In Portugal, thirty-four lived in Porto, ten in Lisbon, and six in Vila Nova de Gaia. In Spain, 579 were from Catalonia, 124 from the Valencian Community, and forty-nine from the Basque Country. Andalusia and Madrid counted with thirty-one Esperantists each.

References

Adresaro de l’kongresanoj (Dresden, 1908).

Adresaro de la aligintoj por la XVa Universala Kongreso de Esperanto, Nürnberg (Nürnberg, 1923).

Adresaro de la kongresanoj en Boulogne-sur-Mer 1905 (Boulogne-sur-Mer : Lajoie, 1905).

Dekdua Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Paris, 1921).

Dekkvara Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Helsinki, 8-16 Augusto 1922) (Geneva, 1926).

Dekoka Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Geneva,1926).

Deksesa Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Geneva 1924).

Dektria Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Paris, 1922).

Dekunua Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Paris, 1917).

Kvina Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Barcelono 5-11 septembro 1909) (Paris 1910).

La adresaro de la kongresanoj (Vienna, 1924).

Listo de la kongresanoj. Deka Universala Kongreso de Esperanto: Paris, 2-9 augusto 1914 (Paris, 1914).

Naŭa Universala Kongreso de Esperanto (Paris, 1914).

Nomaro de la kongresanoj (Cambridge, 1907).

Nomaro de la kongresanoj (Genève, 1906).

Oficiala dokumentaro de la 1ª kongreso de Universala Esperanto-Asocio, Augsburg 1910, Washington 1910 (Geneva, 1910).

Oficiala dokumentaro de la 7ª kongreso de Universala Esperanto-Asocio, Praha, 31 julio-6 augusto 1921 (Genève, 1921).

‘Redakcia Komitato’, Portugala Revuo, No. 2 (14) (February 1914), p. 17.

María Julivert, ‘Esperanto kiel idealo’, Hispana Esperantisto, No. 58 (June-July 1922), p. 71.