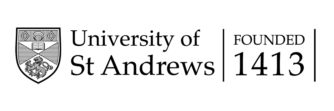

Bonvenon al Aberdeen! Welcome to Aberdeen! This photo was taken in May 1919 on an Esperanto outing at Craibston near Aberdeen in Scotland. I look at this photo with excitement and some late modern historian envy. Envy? Because there is so much, if not too much material to work with. This is true not only for the late modern period but also for research on the Esperanto movement in the early twentieth century. There is an abundance of material. And yet it is full of gaps and holes. Envy? Because I sometimes (but only sometimes) envy my colleagues working on earlier periods where sources are perhaps harder to come by. And yet, these colleagues do fantastic work.

One work, in particular, that inspired this blog post and working with a single source is “Abrahahm’s Luggage” by Elizabeth A. Lambourn. The book takes its starting point and inspiration – well, it is in the title – from Abraham’s luggage. Essentially a single source, a list of long-distance travel luggage and items from around 1150. Building outward from the list the author reconstructs a fascinating story of travel and dislocation in the Indian Ocean world of the twelfth century. This is only a blog and not a book but Abraham’s Luggage serves as inspiration here.

So, my starting point is a single source. A photo, taken in May 1919 near Aberdeen on the East coast of Scotland. And while it is a single source, I would like to use it as a reflection about the Esperanto movement (in Aberdeen as a specific locality) but also more broadly on the wider Esperanto community of the time and how to research it as we do in this project.

Having spent some time with Esperanto and its speakers and practitioners now, a number of things spring to my mind. And it is hard to put them into an analytical order.

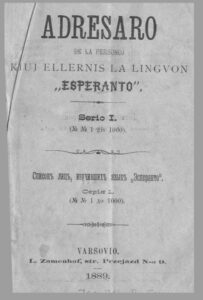

First, I am inclined to say that Ludwik Zamenhof would have been proud to see this group of Esperantists in Aberdeen. Zamenhof had died in 1917. He had not only created the language. He and his collaborators had also pushed hard to organise it around societies, congresses, journals, correspondences, and the systematic attempt to keep track of the movement by collecting names and addresses published in Jarlibros or Adresaros of congresses. Seeing some 38 individuals on an Esperanto outing in Craibston would certainly have made him proud.

Yet, second, the photo raises important question for our project. How did Esperanto end up in more “peripheral” places such as Aberdeen? Who were the local Esperantists? What did local Esperantists do with the language? How did they practice it as a local community but also in connection with other Esperantists elsewhere? This is by no means the only photo of an Esperanto group of the time. We have many others from Copenhagen, to Finland, to local Bohemia.

Third, let us return to the WHO, the people, in this photo. And the inspiration from Abraham’s Luggage. As a single object the photo gives us some clues – and at least as many gaps and questions. From what we have and see we can safely assume that this is a relatively large Esperanto group. We have 38 individuals, we as many women as men. In terms of age, we see teenagers, younger men and women. Some of the men may have just come back from the trenches in the First World War. Was that an inspiration to join the movement? We may not know for sure. Perhaps the oldest Esperantists are a man and a women in there 50s or early 60s – note the lady on the right. Were some of the children there with their parents? We do not know. This is where the clues and the margins from micro history come in. Yet what other sources such as congress lists show is that many Esperantists visited annual congresses as families. A photo such as this (and others) is well-staged. At the time, 1919, this was not a spontaneous snapshot (out of the pocket with a camera or iPhone). This was planned and staged. We may assume that this was a weekend outing – out into nature. The Aberdeen Esperantists are well dressed for the occasion. I am not an expert in fashion, clothing, material culture of the time. Yet it seems fair to assume that these were by and large middle-class Aberdonians. This may have included teachers, a lawyer, a doctor, a clerk, a secretary. The latter would certainly fit the wider social and professional pattern of the Esperanto movement of the time more generally.

Inspired by Abraham’s Luggage and literature around global micro history, what else can we say? How can we connect the photo to other sources and our archival work? And link it with other scales (the jeux d’échelles, to borrow from Jacques Revel) from the biographical and local, to the regional and national and beyond? At a local level, from other sources such as local newspapers, the British Esperantist and the Adresaro de Esperantistoj we can glean that Aberdeen had indeed relatively early on, from 1904 onward when an Esperanto Society was founded, a strong local Esperanto community. Given the size of the city the numbers are disproportionally high compared to other cities, for instance Glasgow. The Aberdeen group is also listed as affiliated to the British Esperanto Association in early 1919. The secretary being Miss Annie L. Burgess.

So we have a photo, lists of names, and in many cases addresses. We cannot (unless someone can help me) match the Esperantists on the photo to actual names on member lists. However, at a local level, names and addresses can be mapped out onto the city space of Aberdeen. This may allow a closer contextualisations of Esperanto in urban and social spaces such as particular areas in Aberdeen. Such an approach is employed at an urban level for Warsaw by Marcel Koschek.